Have you often gone to the gym and just wandered from one piece of equipment to another? You should not – it wastes time, effort, and is the least effective way to workout!

Organizing Your Individual Program

Have you ever designed your own workout? Designing a personal workout program can be intimidating at first. However, with some basic guidelines, you can get started on your first program—a few are already included below as examples to learn from. Each sequential program can then be designed with the benefit of learned experience and it will become easier to plan workout days covering various duration. A workout program can be designed for any realistic period. For example, it is more feasible to design a one-year workout program than a five-year program because one year is convenient and short enough to plan around a schedule of building a solid strength foundation, rank advancements tests, tournament competition, professional fighting events, or other commitments. I mention these because I have long been a professional artist and thus, this article is written from that perspective, as well as from bodybuilding, ball sports, military fitness, CrossFit, general fitness, speed-strength, and others that I have been involved in training individuals for over a long period of time. The principles discussed below work for any fitness or training regimen. Have fun, and remember, before you begin your resolutions for 2018, write them down and attack them one at a time!

To effectively design your own program, you must know what yours goals are for a yearly training period. Are your goals to simply increase speed and strength? Will you be competing in tournaments or fighting in professional events? Your program must be designed around periods of time in which an all-out effort will be required. For example, if you were going to compete in a fight on Saturday, how will you train for it the week before or the week of the event? Should you be doing more strength training or more event specific training? Also, suppose you were fighting each weekend for several months, started back on your normal strength program and after six or eight weeks were invited to a tournament in Europe. How would you work this unscheduled event into your yearly training program? How would the daily-workout cycle change? The workout cycle is the change of intensity of lifts done in the workout—this will be discussed later. Without further ado, let us begin.

Two Types of Programs

There are two kinds of programs that you can design: (1) non-competitive and (2) competitive. A non-competitive program assumes you are not competing in the ring, tournaments, rank advancement, or other fighting events, but are primarily working on increasing speed and strength. A competitive program assumes you are testing for rank advancement, competing in free-style sparring events, entering professional full contact fights, or other competitive events.

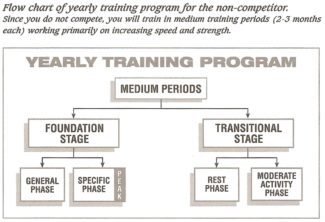

To left is a flow chart of a yearly program for the non-competitor. Because you do not compete, you will train in medium training periods (2-3 months each) working primarily on increasing speed and strength. Time will be your friend.

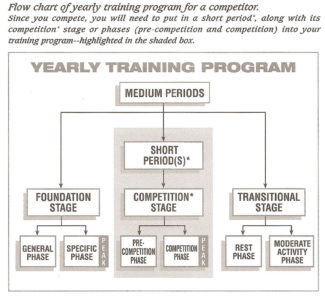

Regardless of type, a program needs to consider stress placed on the body, rest, and recovery as the essential basics. Every part of the program, which will consist of periods, stages, and phases, must consider these basics. The workout program itself can be separated into three parts: (1) the yearly training period (commonly referred to as a macro-cycle); (2) a medium training period lasting two to three months (commonly called a mesocycle); and (3) a short training period lasting one to two weeks—micro-cycle (needed only for a competition program). Further, each of these periods will have a foundation, competition (for competitive program), and transitional stage. Before beginning, study the two illustrations (just above for the non-competitive MMA and below for the competitor) of a yearly program and its related periods, stages, and phases. While a yearly program is complex, it can be simplified by separation into shorter training periods as mentioned above.

The highlighted middle section of the flow chart to left is of a yearly training program for a competitive MMA. Since you fight competitively, you will need to put in a short period* along with its competition stage* or phases (pre-competition and competition) into your training program—highlighted in the shaded box. Based on competitive cycles, time may not be your friend.

Kim’s Program (Beginner Level)

My friend Kim says, “Okay, I understand that we will be discussing reps, sets, volume, intensity, periods and many other specifics later, but how do I write my own program now?” How can I set my maximum weight (goal) to lift for each exercise and what exercises should I do?

These are valid questions and are like those I am asked many times per week. After discussing Kim’s goals with him, I discovered two basic, but essential items of information. Kim is a beginner at strength training and she is also, currently, a non-competitive MMA. However, he does want to compete next year; she also weighs about 140 pounds. Because Kim is a beginner and will need to learn proper lifting technique; she will primarily use dumbbell weights in her first programs. Using dumbbells will allow her to use lighter weight, but will effectively teach proper technique without overly risking injury.

So, let us help Kim design her program. There are several additional things we need to know, but let us list all the criteria we need for helping Kim write her program first. Following are the criteria necessary for Kim to adequately design a personal workout:

Criteria Questions for Designing a Personal Workout – this example is a beginner-level MMA workout

1. What duration should Kim’s first program be (in weeks)?

2. Each program will have a peak at the end where he will lift his maximum set weight (goal) for each exercise. Thus, how many small programs should Kim write for an entire year?

3. Will he compete this year? This will affect individual program length.

4. How many days per week should Kim lift?

5. How many exercises should be done each day?

6. Which exercises should he perform for each workout?

7. What order should these exercises follow?

8. How many reps (repetitions) and sets should he do for each exercise?

9. How much weight should he lift in each exercise?

As you can see, the above questions each add in complexity of designing a workout, especially if it is for a professional. Following is how Kim decided to write her program (in order of questions asked):

(1) As a beginner Kim should write only a two to four-week program; she chose to write a four-week program.

(2) This four-week program can be repeated two or three times and utilized as an 8-12-week program. Since she will need to rest from his workouts occasionally (transitional phase—see figure 3.2) Kim would need only 3-5 of these small programs to make up a yearly training period.

(3) We already know the answer to this question; Kim is not competing this year, but may do so next year. Thus, her program design will be relatively simple, and she will work primarily in a foundation stage—a general period of building overall conditioning and increasing speed and strength (to be explained later).

(4) Because Kim is a beginner and has never done any strength training before, she is going to lift only three times per week: Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. This will decrease any chance of fatigue.

(5) As a beginner, Kim has decided to do about five to six exercises per day, both because she will be using light weight and because this number of exercises will work her entire body, building a good strength foundation—remember, the goal in speed strength is not to work body parts as in bodybuilding, but to work the entire body so it will perform as a unit.

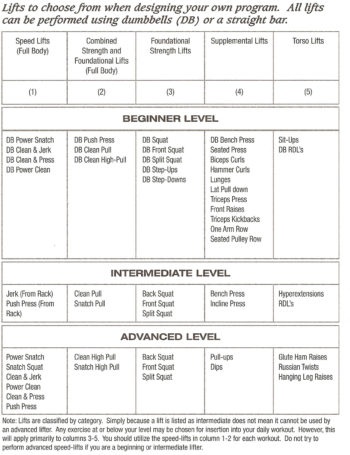

(6) Since Kim has a handy table that is separated into columns (see below), she knows from what I have told her, that she can simply pick one exercise, sometimes two, from each column at the beginner level for her daily workout. This depends upon whether the exercise is a full body speed lift, supplemental lift, a combined strength and foundational lift, or a torso lift (more on this later). For each workout day,Kim will simply choose a lift from each column (beginner level) listed that was different from the lift chosen from that same column for the previous workout day.

(7) The order of the lifts should be the fastest to the slowest exercise. The table lists the fastest exercises in column (1), next fastest in column (2) and slower exercises in the remaining three columns (3-5). Also, the first exercise in column (1), dumbbell (DB) snatch, is the fastest proceeding to the slowest at the bottom of the column. Tim has learned that he should do his fast exercises first, followed the by next fastest on down to the slowest exercise on each workout day. He knows not to mix slow exercises between fast exercises, which help avoid injury.

(7) The order of the lifts should be the fastest to the slowest exercise. The table lists the fastest exercises in column (1), next fastest in column (2) and slower exercises in the remaining three columns (3-5). Also, the first exercise in column (1), dumbbell (DB) snatch, is the fastest proceeding to the slowest at the bottom of the column. Tim has learned that he should do his fast exercises first, followed the by next fastest on down to the slowest exercise on each workout day. He knows not to mix slow exercises between fast exercises, which help avoid injury.

(8) Initially, Kim will perform only 4-12 reps per set and 3-6 sets per exercise. This will be sufficient for obtaining a good foundation. However, the number will change when Kim adds more weight, decides to start competing, or uses the straight bar instead of the dumbbell. More specifics will be discussed about this later in the chapter.

(9) How much weight should Kim use? This is a difficult question to specifically answer; however, for the first couple of programs, light weight should be used. For example, one of my students weighs 270 pounds, but started with just the straight bar (45 pounds) because these lifts are more difficult and require more focus than bodybuilding lifts. A general rule of thumb is set your maximum weight for most slow exercises (squats and presses) to about 80 percent of your total body weight. If you are a beginner, do not set a weight for any exercise until some familiarity with the lifts has been attained. For fast exercises (snatch, clean and jerk, pulls, etc.), a maximum weight of about 25-50 percent of your body weight is recommended; 25 percent for beginners and 50 percent for advanced lifters. For supplemental lifts that work primarily one joint such as front raises, triceps kickbacks, etc., use a small weight (as little as one pound) and increase to a comfortable weight for each set. These types of exercises do not necessarily need to have a maximum weight set for them. Another method for setting a max goal weight is to select a weight you can lift for three sets of five repetitions for exercises such as the bench press, back squat, etc., and then add 20-40 pounds to this weight load to obtain your max.

Regardless of method, if your initial weight seems too heavy, decrease it, especially for fast exercises. Again, try different weights and get comfortable with the exercises before you attempt any heavy weight. If you already have lifting experience, it will be easier for you to select an appropriate weight because you already know them for some of the exercises you will do. Once you have selected this weight, it is your goal weight (100 percent) for a given exercise. You will not attempt to lift your goal weight until the last week of each program. For Kim, 120 pounds would be her max weight in the squat, which she would work up to over a period of 8-12 weeks; this would exclude her first program, so the time would be longer.

Regardless of method, if your initial weight seems too heavy, decrease it, especially for fast exercises. Again, try different weights and get comfortable with the exercises before you attempt any heavy weight. If you already have lifting experience, it will be easier for you to select an appropriate weight because you already know them for some of the exercises you will do. Once you have selected this weight, it is your goal weight (100 percent) for a given exercise. You will not attempt to lift your goal weight until the last week of each program. For Kim, 120 pounds would be her max weight in the squat, which she would work up to over a period of 8-12 weeks; this would exclude her first program, so the time would be longer.

At this time, I would like to give a little advice about increasing your maximum or goal weight. At the end of each program, you will be able to increase your max (goal) weight by perhaps 5-10 pounds for small muscle groups (triceps, biceps, etc.) and 20-40 pounds for large muscle groups (legs, chest, back, etc.). However, this would be at the beginning. As you progress to the intermediate and advanced lifting levels, the increase would be much smaller, there may be no increase. The time will come when you will reach your maximum lifting potential, this is something you will have to judge for yourself.

Kim has designed her program and it appears in the two tables below. For week 1, day 1 her first to last lift was chosen as follows: (1) the dumbbell clean pulls from column 2; (2) the dumbbell squats from column 3; (3) the dumbbell standing press, front raises, and hammer curls from column 4; and (4) the sit-ups from column 5. Notice that Kim did not choose the very fastest lifts, the snatches or clean and jerk from column 1 in the table above as the first lift in her program for the first day.

This is a wise decision because it lets her break into her program slowly without risking injury. On each successive workout day she followed a similar pattern. In week 1, day 2, her first two lifts were from column 1 and so on. Each day, the lifts changed; Kim automatically added variety to her program. This will reduce boredom, your worst enemy.

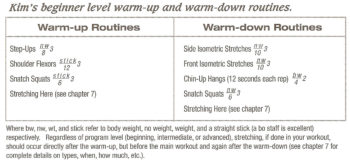

At the end of each program, Kim will take a few days off; she will go into the transitional stage (first graphic in article – above). Her program, as a non-competitor, was the foundational stage. Also, each day, you must warm-up before working out and warm-down after the workout. Kim’s warm-up and warm-down routine is listed below. Additionally, to maintain intensity during the workout, Kim will attempt to complete each workout, including warm-up and warm-down routines in 60-70 minutes. This is not difficult to do, but you must use your time efficiently and rest between sets – not talk to your friends!

Yearly Training Program

Now that we have helped Tim write his program, let us discuss program specifics. Tim wrote his program based on simple questions and selections of exercises from tables. What are the details behind these selections and program design? First, I will discuss generalities of the yearly program, followed by specifics of periods, stages, and phases. The yearly training program is one full year of training for the MMA that includes sparring work, heavy bag work, speed-strength training, sport-specific training, belt examinations, competition or other events. However, it is difficult to write a yearly program unless you have experience; even then, it is a daunting task. The primary concern for the yearly program is when different events may occur that need to be planned into your program.

To mention it again, regardless of what kind of program you write for yourself or have someone like a trainer do for you, it is very important that you warm up prior to beginning your main workout and warm down after it is completed. Kim’s beginner level warm-up and warm-down routines are shown below.

A yearly training program should be separated into two different kinds of training periods (a medium training period and a short training period) that will allow you to train for either general speed-strength, if you are a non-competitor (like Kim) or, as a competitor (see first two figures in article – above), or, for specific events such as tournaments. Regardless of your fitness and training level, always keep track of your progress so that you can keep improving as you work toward your goals. (Portions of this article were extracted from Speed-Strength Training for MMA: Fighting Power).

A yearly training program should be separated into two different kinds of training periods (a medium training period and a short training period) that will allow you to train for either general speed-strength, if you are a non-competitor (like Kim) or, as a competitor (see first two figures in article – above), or, for specific events such as tournaments. Regardless of your fitness and training level, always keep track of your progress so that you can keep improving as you work toward your goals. (Portions of this article were extracted from Speed-Strength Training for MMA: Fighting Power).